Differentiation. Diverse learners. Individualized education plan. Resource room. Special education.

What do we think about when we think of these terms? How are we — as teachers crafting lessons, resource room specialists supporting students, and administrators looking at curriculum design and course schedules — taking into account the varying needs of our students?

A Visit to Luria Academy and Room on the Bench

I recently had the privilege of visiting The Luria Academy, a Jewish Montessori school in Brooklyn, NY. Luria has a unique approach to meeting the needs of diverse learners, and that’s thanks in large part to Dana Keil, the school’s Director of Special Education and one of the fellows in my Joshua Venture Group cohort. Dana’s venture is called Room on the Bench, and it helps Jewish schools implement fully inclusive special education programs.

This is the type of program I saw at Luria when I visited with Naomi Weiss, who works with me at Magen David Yeshivah High School, supporting teachers in implementing the latest pedagogies, including those that include differentiation. Naomi and I were joined by Shelley Cohen, a relative of mine who founded and runs the Jewish Inclusion Project, which trains rabbis and educators in creating fully inclusive programming.

What Naomi, Shelley, and I saw at Luria was truly inspiring. The school has all the mainstays of the Montessori educational approach: students, grouped by age in multi-age settings, are taught to take ownership of their learning and become reflective about it. The students progress in their learning at their own rate, working alone or in small groups to master material and move through the daily and weekly assignments they have. Peer learning is common, and a peace and calm pervades the classrooms and school.

I loved this inspirational message tacked on to a classroom wall at Luria, where all students learn executive functioning skills. The school is filled with posters about crucial life skills such as follow through, staying on task, and conquering procrastination.

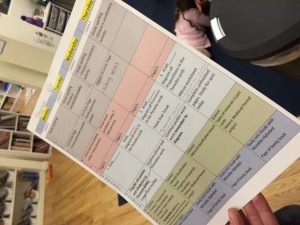

Every student at Luria receives a sheet with his/her weekly tasks, and they move through the work in the same way an employee might, taking ownership of and responsibility for their learning. The fact that all learners need that kind of life skill, not just diverse ones, was a topic of conversation over a Shabbat meal I recently had with parents.

Perhaps this is why a fully inclusive program works so well in the school: the model means everyone gets “special” attention and an individuated learning plan. When an occupational, physical, or speech therapist or reading or other learning specialist enters the Montessori classroom, it isn’t an intrusion; it’s just a seamless part of a bustling and active room in which a myriad of learning experiences are occurring. One more doesn’t attract attention or seem out of place.

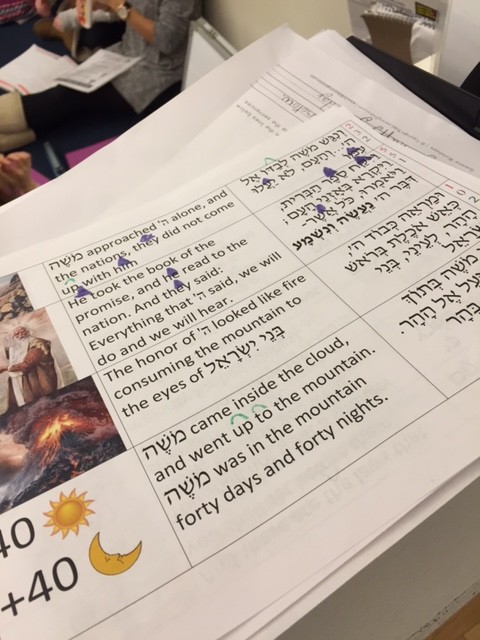

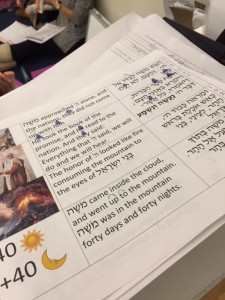

The grammar blocks are used to reinforce skills in English and Hebrew language. This interdisciplinary type of thinking reinforces learning for ALL students.

All Learners are Diverse

Education is now embracing models which emphasize personalized, self-directed learning and collaboration among peers, and as a result teachers’ roles are changing: educators are being asked to facilitate the learning that goes on in the classroom, not simply by standing in the front of the room, but by circulating among students who are involved in multiple tasks. In short, education is becoming a bit more Montessori-like, and that means we have an opportunity to rethink what we mean when we use terms such as differentiation, diverse learners, individualized educational plan, and special education. We have a chance to create a classroom that is a lot more democratic, one that is genuinely diverse, and not one that simply uses the term as a gentle euphemism.

Differentiation at the High Tech Schools

On February 25, I’m going to be meeting up with a group of Jewish educators who are visiting the High Tech public charter schools in San Diego, CA. These unique schools, founded and run by Larry Rosenstock, have a similar approach to differentiation as Luria does. That is because, as Larry has said, the foundation of his school is not a particular pedagogy or even the beautiful work that is the hallmark of the High Tech brand.

As Larry explains, the foundation of his school is equity: the idea that each student should have the same access to education and opportunities within it as any other. This is manifested in the school’s complicated algorithms that ensure a student in an underrepresented zip code gets chosen in the lottery system the public schools have established for its charter schools.

Over winter vacation, Magen David’s Associate Principal Mrs. Sabrina Maleh and Yeshivat Noam’s PBL expert and Middle School Science Teacher and Curriculum Designer Ms. Aliza Chanales did a winter residency at the High Tech schools. They had a chance to ask the special education teachers what it was like to teach at the schools, and the teachers were honest: they said it was sometimes difficult to get all the students to perform at the same level and complete the kind of high-quality work the school is famous for. So the fully inclusive model is not without its challenges.

Its benefits, though, are pretty impressive. On my first visit to the High Tech schools, this past June with Dr. Eliezer Jones, Eliezer and I spoke with middle school math and science teacher Marc Shulman. He told us about the way he differentiates math lessons in his fully inclusive class, noting some of the challenges he encountered in the process. But he also told us that because all the students are in the same classroom, once the math lesson is over and the class has moved on to another task, such as woodworking — a particular favorite of his — some students who were less proficient at math suddenly found themselves shining in the new activity. And some students who shone when they could do math on paper suddenly struggled when they had to apply it to the physical world. He watched as the roles of those who were expert and those who needed support were reversed.

When we silo kids from each other, putting them in fixed tracks and not letting them see each other in multiple settings doing tasks that trigger various modalities of thinking and doing, we may end up labelling students — and, worse, letting them label each other. These labels can be harmful in so many ways. One of the ways is that they make students believe they are not “smart.” We’ve been hearing a lot lately about Carol Dweck’s fixed vs. growth mindsets, and in the February 21-22 issue of the Wall Street Journal, Alison Gopnik writes about IQ and the fact that “[s]cientists have largely given up on the idea of ‘innate talent,’ a “change that might seem implausible and startling.” However, Gopnik explains:

Biologists talk about the relationship between a “genotype,” the information in your DNA, and a “phenotype,” the characteristics of an adult organism. These relationships turn out to be so complicated that parceling them out into percentages of nature and nurture is impossible. And most significantly, these complicated relationships can change as environments change.

Gopnik adds:

James Flynn, at New Zealand’s University of Otago, and others have shown that absolute IQ scores have been steadily and dramatically increasing, by as much as three points a decade. . . . The best explanation [for the phenomenon] is that we have consciously transformed our society into a world where schools are ubiquitous. So even though genes contribute to whatever IQ scores measure, IQ can change radically as a result of changes in environment. Abstract thinking and a thirst for knowledge might once have been a genetic quirk. In a world of schools, they become the human inheritance.

Gopnik says, “Thinking in terms of “innate talent” often leads to a kind of fatalism,” but she states that the actual science of genes and environment means that if “we want more talented children, we can change the world to create them (my italics).”

Makers in Israel have started gathering for Tikkun Olam [Fixing the World] Make-a-Thons to help those with disabilities become as the video below says “closer to life.” I love that phrase. We all want to live “closer to life.” If we’re using language such as resource room and special education to distance students from the center of the learning experience and therefore from life, then we aren’t doing them justice. We need to rethink the way we enact diverse learning in Jewish day schools, and we should be assured that doing so is really quite a Jewish notion, given the deep sense of justice that permeates our religious life.