Rigor in PBL

One thing I [Tikvah Wiener] keep getting asked as I employ project-based learning (PBL) in my classes is this:

But do the students write enough? Are they doing enough essays? Is PBL in general rigorous enough?

I understand where the concern comes from, and believe me, I’m on it. The students in my tenth and eleventh grade English classes have just finished a flurry of writing activity, a lot of it very traditional and as academically rigorous as any you’d expect in any English course.

A Doll’s House

Example: in my tenth grade English class, students just finished revising a short piece analyzing A Doll’s House by Henrik Ibsen and then comparing it with The Merchant of Venice, which we read earlier this year. Here’s a sample, a particularly good essay that Julia wrote:

A Doll’s House, by Henrik Ibsen, is a play about a woman, Nora, who slowly realizes that her husband, Helmer, doesn’t treat her with respect. In A Doll’s House, several quotes show how a woman is considered lower than a man. In the play, Ibsen is socially critical of this view.

In Act One, Nora is worried about the dress she is going to buy for a dance. When she tentatively asks Helmer if he would help her pick one out, he says to Nora, “Aha! So my obstinate little woman is obliged to get someone to come to her rescue?” (26). There are a few things about this quote that show how Helmer has no respect for Nora. First, there is the way he addresses her as “my obstinate little woman.” To him, Nora is a little, stubborn pet that belongs to him. There is also the way that he says “Aha,” as if he was expecting that Nora would need something from him eventually. Lastly, there is the overall sentence and the stereotype in which Helmer casts Nora, which is as a damsel in distress. He right away recognizes that Nora needs his help and escalates it to “rescue.” To Helmer, Nora’s requests are childish and small, so his responses back to her are mocking.

In Act Two, Nora makes a work-related suggestion to Helmer. This time, Helmer is more aggressive in his belittling of Nora. He exclaims, “Is it to get about now that the new manager has changed his mind at his wife’s bidding?” (35). He implies how ridiculous it would be for a simple housewife to give input on a work matter. Helmer is also concerned with what people would think of Nora helping him. This proves that society as a whole viewed the idea of a woman doing more than household jobs as embarrassing and foolish.

In Act Three, Nora finally rises above what society thinks of her and doesn’t let it define her. She answers Helmer, who told her she didn’t understand the world’s conditions, by saying, “I am going to see if I can make out who is right, the world or I” (69). She understands the way that society perceives women, but she no longer wants to abide by it. Rather than being the perfect wife and mother who would never abandon her family, she walks out the door to become independent. It is possible it will be difficult for her to adjust to her new freedom and that society will look down upon her, but Nora takes a big step by realizing she wanted the freedom in the first place. Though one could view her statement as her being unsure who is right, it could really be viewed as Nora knowing that she is right but wondering if the world can accept it also, or if she must rise above society totally on her own.

In The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare is also socially critical. Portia, the play’s heroine, must disguise herself as a man in order to become a lawyer, since women couldn’t have such jobs in Elizabethan times. In A Doll’s House, Nora disguises herself the opposite way Portia does. Rather than being her true self, Nora takes on the identity of the perfect woman society wants her to be. On the other hand, Portia pretends to be everything society doesn’t want her to be. At the end of The Merchant of Venice, Portia doesn’t need to disguise herself. She is sly and holds all the power over the men of the play. At the end of A Doll’s House, Nora takes off her mask and joins Portia in going against society’s stereotypes and becoming the independent woman she wants to be.

Sonnet Explication

Also in my sophomore English class, students are in the process of writing a 2-3 page essay on one of Shakespeare’s sonnets. The students must include in their analysis at least two sources of literary criticism, one by Helen Vendler, who is, some would say, the foremost poetry critic in the US today. She teaches at Harvard and has written a comprehensive, Formalist analysis of the Bard’s sonnets. Here is a student work-in-progress. In this version of the paper, Zach has written a short analysis of the sonnet he is studying and has included Vendler’s take on the poem, though he hasn’t cited her work yet. Recently, in edmodo, I posted a link to the OWL Purdue Writing Lab, which explains exactly how to cite according to MLA Standards.

Here is Zach’s work:

The main theme in Sonnet 30 is recollection of the past. Throughout the sonnet, Shakespeare expresses the grief he feels as he “summon[s] up remembrance of things past” (2). One very prominent literary device the sonneteer employs in this sonnet is imagery. Shakespeare uses words such as “sessions” (1), “summon up” (2), “cancelled” (7), “expense” (8), and many others in order to make it seem as if his recollection experience is like a court case, and that he is ‘judging’ his past. Shakespeare divides the time frame of the sonnet into two groups. The first is the present, and the second is the past, which is subdivided into four more parts. While in the present Shakespeare stresses the fact that the grief he feels is new, regardless of the fact that he had already once grieved over the same grievances. He demonstrates this by contrasting old and new, (“with old woes new wail” [4]), as well as switching from locutions in which the second use of a verb or noun positively intensifies the first one (i.e. “grieve at grievances” [9]), to negatively (i.e. “new pay as if not paid” [12]). The four time frames of the past are the original neutral time pre-happiness, the happy time, the times of loss, and the time of stoicism where Shakespeare’s soul hardened, and he did not cry.

The concept that Shakespeare’s thoughts are successive and overlap is also demonstrated through the sonnet itself. The repetition in quatrain 3 of “grieve at grievances foregone” (9), “fore-bemoaned moan” (11), and “new pay as if not paid before” (12), coupled with the multiple phonetic concentrations of “thought-strings” (such as sessions, sweet, silent, summon, sigh, sought, sight, since, and sad) that are dispersed through all the ‘time periods’ of his life, both demonstrate Shakespeare’s constant overlapping thought process. Shakespeare even takes it a step further and portrays an increasing psychological involvement as the quatrains progress. The grievances go from general (“many a thing” [3]), to specific (“precious friends” [6]), to intensified (“grieve-grievances” [9]). These successive phases of feeling overlap because of the similarity in their lexical and syntactic concatenations as if they were all one long process each causing the next. This fluidity among time periods, thought processes, and feelings all relate back to the mentality of man, where Shakespeare is trying to show how man’s thoughts are constantly overlapping and build off of each other.

To illustrate how deep the learning goes — and the material the kids are studying here is pretty traditional fare — I’ll share a conversation another student — Jonah — and I had as we worked on his sonnet together. Jonah is dissecting Sonnet 143, a mock epic which has Shakespeare comparing himself to a baby chasing after his mother who is chasing after a chicken. The farcical situation reflects a love triangle in which the poet finds himself in the “infantile” (get it?) position of not giving up on his crush, even though she clearly doesn’t want him:

Lo, as a careful housewife runs to catch

One of her feather’d creatures broke away,

Sets down her babe, and makes all swift dispatch

In pursuit of the thing she would have stay;

Whilst her neglected child holds her in chase,

Cries to catch her whose busy care is bent

To follow that which flies before her face,

Not prizing her poor infant’s discontent;

So runn’st thou after that which flies from thee,

Whilst I thy babe chase thee afar behind;

But if thou catch thy hope, turn back to me,

And play the mother’s part, kiss me, be kind;

So will I pray that thou mayst have thy ‘Will’,

If thou turn back and my loud crying still.

After Jonah and I had noted Shakespeare’s allusions to epic poetry and Chaucer as well as Vendler’s comments on the repetition of words such as runs, catch, cries, and flies, Jonah remarked, as we dissected the simile, that just as Shakespeare feels excluded by his beloved, so he excludes himself from the sonnet, instead making most of the sonnet about the simile and not about himself. That’s an AWESOME close reading, Jonah! Well done!

But Wait, There’s More . . .

In a PBL class, however, there is more to learning than simply writing essays. Understanding the literature and showing mastery of the material in an essay is simply the first step towards a larger goal: creation of new content. For example, once students are finished writing their essays on

A Doll’s House, they have to post it on the Shakespeare website we created earlier in the year.

Here is Zach’s page which features his essay comparing how Ibsen and Shakespeare depict wealth and honor in their plays. And

here is Sam’s page which discusses law and mercy in

A Doll’s House and then compares how the ideas are developed in Ibsen’s play and

The Merchant of Venice.

Not only are students in my class motivated to revise their work for a better grade — an opportunity I often offer them — but I correct the essays with a different eye, knowing they can be seen in a visible place. Feel free to explore the bardofparamus website, where my fellow English teacher Rabbi Dan Rosen is also currently having his students post their work on The Merchant of Venice and where another Frisch colleague, Mrs. Meryl Feldblum, also had her students work.

Because the students organize their work around topics — in the case of the Shakespeare website, for example, the topics connected with major themes of the plays and sonnets — they become familiar with those ideas and spiral around them for the rest of the year, drilling deep into them as they see how they apply to all the works they read. Therefore, rigor ensues not only from essay writing but from using digital media to juxtapose works in surprising ways that attract the students’ attention.

Final-ly

Last year, after a year of “un-schooling” my course,

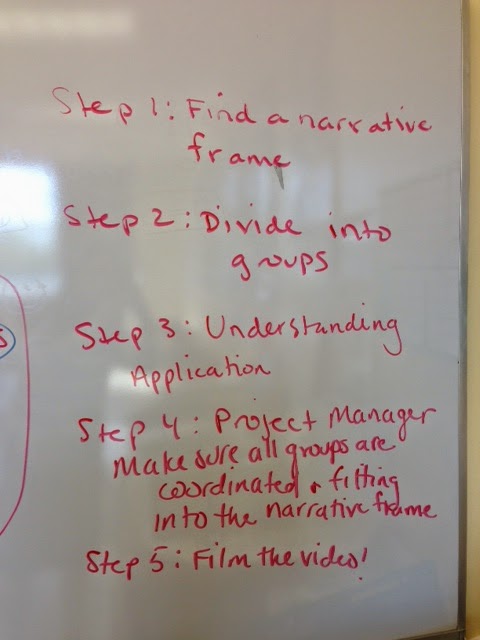

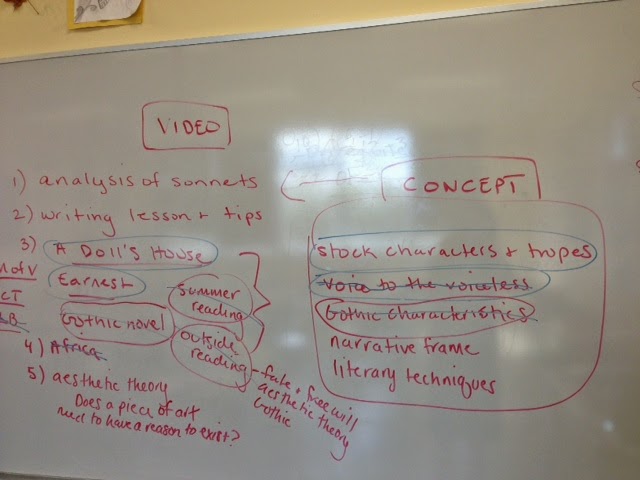

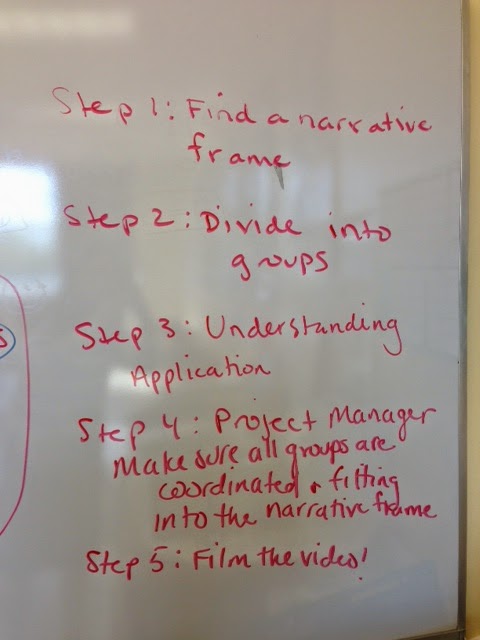

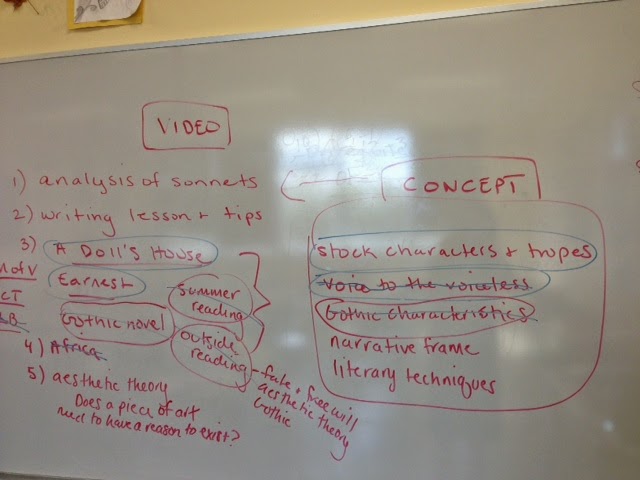

I wrote about the Twitter final that was a result of the class’ desire to undertake a non-traditional assessment. This year, a year that was even more PBL-ed than last, my class felt strongly that they wanted to be creators of a final, not simply consumers of one. We’ve been working for the last two weeks on a collaborative project: a script for a video that will be a satirical look at our year in English, satire being a genre we studied repeatedly. We also focused on narrative frames consistently, so the students agreed to create one together and then break off into smaller groups to tackle various concepts we’d studied throughout the year (Take a look

here at the syllabus, which did see some changes as the course unfolded organically). Since my daughter is in the class, the narrative frame became this:

My daughter Lila — who is now married to a classmate — and I are heading to a family reunion. We keep having flashbacks to her tenth grade year, with my remembering the serious study we did of texts and genres and her remembering what really went on in class!

|

| The process of deciding what our final would be! |

|

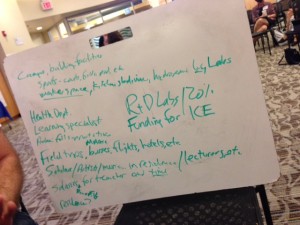

| We chose topics and then applied the texts we studied to those concepts |

I can’t tell you how excited the students are to work on this project. They feel empowered about being creators and enthusiastic about their learning.

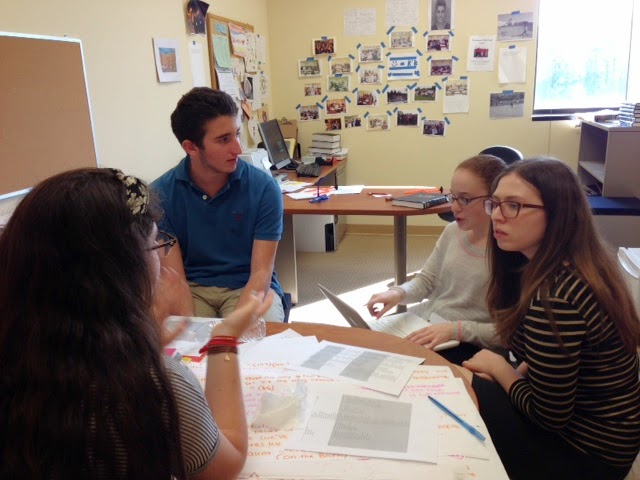

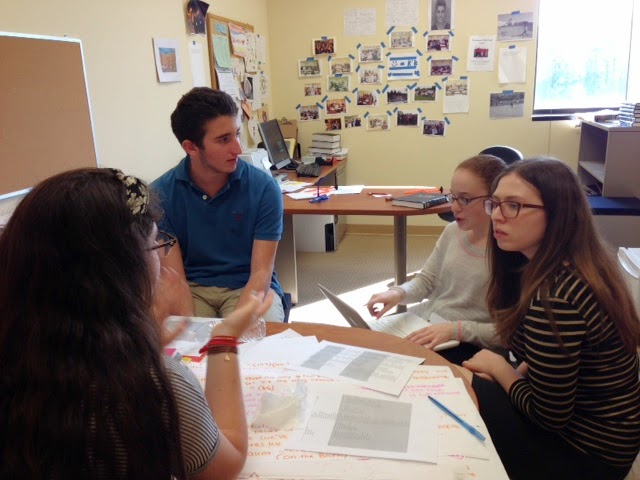

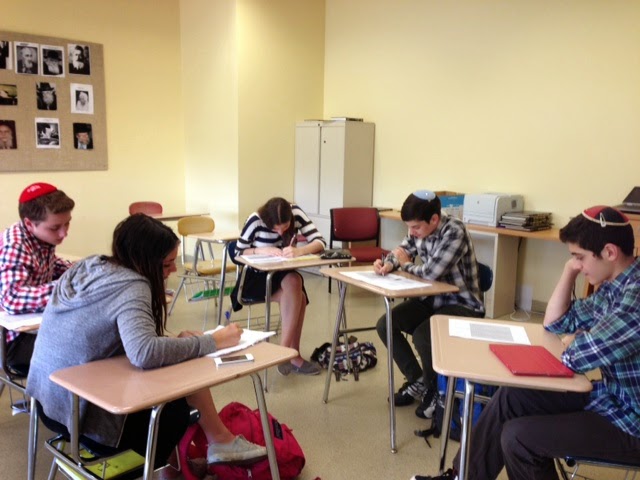

|

This group is focusing on stock characters and plot devices in works

throughout the year, even including Shakespearean sonnets in their script.

You can see the rubric for the final on the desk. As David said when he

saw the rubric, “The script really has to show learning, then.” Yes, it does! |

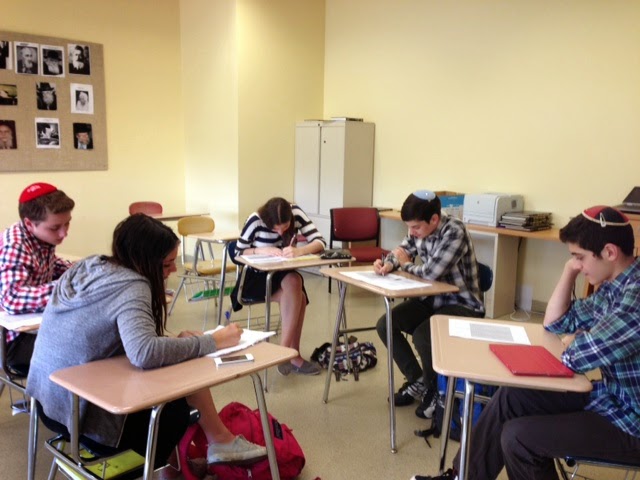

|

This group is satirizing the idea of how literature gives voice to the voiceless,

a topic we discussed at length over the course of The Frisch Africa Encounter.

Some ideas bandied about for their satire: Obama and the Nigerian president

call Frisch to thank us for our incredible and revolutionary work!

Also in the works: a song to “Under the Sea” discussing women’s

traditionally having no voice in his-story. |

In order to make sure real learning would occur, I created a rubric for the project, which you can view below. I love hearing the different groups discuss how to get their sequence into the 9-10 brackets. #gamifyingclass

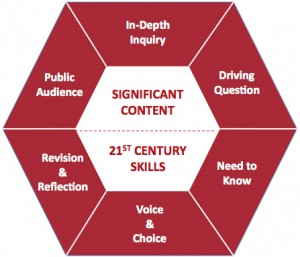

I get asked a lot about rigor in PBL: as I said in my Google Hangout with Ken Gordon and Lisa Colton, when we spoke about passion-based learning in education, whoever thinks PBL can’t be rigorous hasn’t found the right resources. My go-to places are edutopia and Buck Institute of Education, and of course I’ve been deeply inspired by High Tech High in San Diego, CA. It’s not a simple or easy thing to transform a course into one that uses PBL, but I guarantee, when you see students discover how deeply they can think about an idea or the power in being creators, that it’s completely worth it.

Rubric for Final