This past month has been an exciting one, filled with diverse learning experiences, and it’s reminded me of the importance of challenging oneself by leaving one’s physical and mental space. The month began with a trip I took with my colleagues at Magen David Yeshivah High School, Associate Principal, Ms. Sabrina Maleh, and Director of Educational Technology, Rabbi Michael Bitton. Sabrina, Michael, and I traveled to Silicon Valley where we met up with Stanford University doctoral candidate and JEDLABian Matt Williams [You can also catch Matt on the Summer Sandbox videos; he facilitated this year’s Sandbox and led workshops on culture change on Day 3].

Matt generously set up tours and meetings for Sabrina, Michael, and me, giving us insight into the many facets of workplace culture, Design Thinking, Maker Spaces, Fab Labs, and project-based learning that we were setting out to explore.

Day 1

On Monday, November 3, after a hearty breakfast at Izzy’s Brooklyn Bagels, Matt, Sabrina, Michael, and I set out for a tour of Google headquarters.

Google interested us because we wanted a look at its workplace culture, and we weren’t disappointed. As you can see from the entry point we posed in front of, the place has a Disneyland-for-adults feel that is echoed throughout the complex. Though I’m not sure if Google employees think it’s the happiest place on earth, the company does aim to keep its workers content, a fact that’s apparent from the Adirondack chairs scattered in casual groupings in outside spaces to the volleyball court set up near the employee-run herb garden. A mobile barber shop was parked in one parking lot, and a laundry room enabled employees to do their wash throughout the day. Of course the fitness room was state-of-the-art, but the biggest talking point — one that I heard repeated often — was the fact that Google has a rule that no employee is allowed to walk more than 150 feet without encountering (free) food. Yes, a Weight Watchers branch had to open onsite, mostly for first-year employees who hadn’t yet learned how to ration.

My one question as we left Google was whether the company was catering to employees in order to create whole-person well-being or because workers needed so many amenities because they didn’t have a home life. . . . I don’t have the answer yet, but here are some of the things I enjoyed hearing and seeing about the most:

Yes, that’s Michael Bitton at the helm of a giant Google Earth, honing in on various parts of the world, including Israel and NY

An employee-run herb garden is only one of the many passion-based “hive communities” that have popped up at Google. All are self-run, with their own listservs and protocols.

Larry Page and Sergey Brin, Google’s founders, conduct weekly town hall meetings, where they share news and let employees voice ideas and opinions. Yes, the color scheme is consistent throughout the complex. You will find no purple at Google, and you’ll find company bikes that are painted in the famous Google palette.

Google was exactly what I thought it would be — though with a larger gift shop that carried a broader range of goods than I had anticipated. Still, hearing about Google’s famous culture and seeing it up close were two different things, and I was grateful for the trip into one of the epicenters of innovation. I have to remain positive: remember, everything I’m typing right now is being picked up by one of these:

Professor Lee Shulman

After Google, our next stop was a meeting with Dr. Lee Shulman, educational psychologist, professor emeritus at Stanford University, former president of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, and past president of the American Educational Research Association (yes, this is all one person). Professor Shulman also happens to be a warm and witty man who graciously shared his wisdom and advice with us. Speaking with us for well over an hour, he told us to tackle culture change by looking at obstacles as opportunities. We’ve been using Lee’s growth mindset language ever since we left his office. You can get to know Professor Shulman and gain from his positive, humorous, Jewish, and cold-cut-filled take on life through his writings, some of which are more insouciant than others.

Stanford University’s d. School

After leaving Professor Shulman, we then headed to Stanford University’s d. School. Let me give this place some context: I have been slightly obsessed with the d. School ever since I saw David Kelley’s TED Talk, ” How to Build Your Creative Confidence.” Seeing that Talk led me to investigate all things IDEO, Kelley’s firm which employs Design Thinking, and that led me to the d. School, the Design Thinking school Kelley started at Stanford, with Steve Jobs’ blessing (Kelley and his firm designed products for Jobs for over 20 years. Apple’s first mouse? Designed by IDEO).

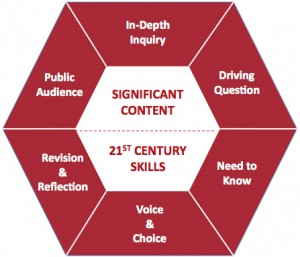

Design Thinking

Here’s a brief explanation of what Design Thinking is:

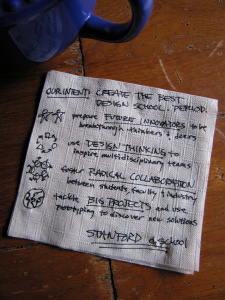

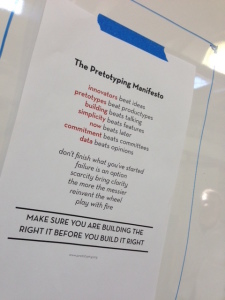

And here’s the d. School manifesto, on a napkin.

Know, too, that Maya Bernstein of Upstart Bay Area has been working with the Jewish Education Project in NY to bring Design Thinking to Jewish education. We’ve been talking Design Thinking on JEDLAB lately as well, so join the conversation there.

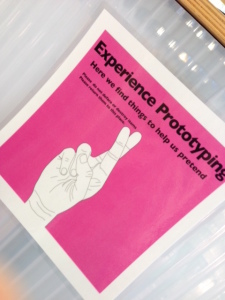

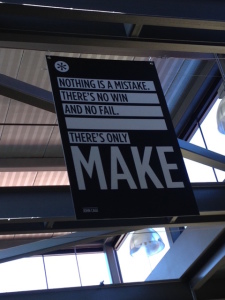

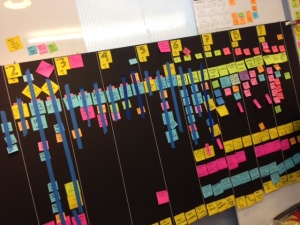

Seeing the d. School in person did not disappoint. It was every bit as sharp, fun, and packed with post-it notes as the videos and websites make it out to be, and the fact that it now has a Maker Space only makes it that much more appealing. I also enjoyed seeing a prototyping cart with all sorts of random objects on it that reminded me of the seemingly useless items now filling the shelves of my office but which I am confident will one day be used in creatively cutting edge ways by Magen David teachers and students. Here’s a glimpse of the d. School, with its emphasis on ideation, prototyping — in both analog and digital form — and failing fast to fail forward:

I love this: can you see the bottom? It says, “Maker sure you are building the right it before you build it right.”

Eco-friendly Silicon Valley makes way for the stickie-note-obsessed d. School!

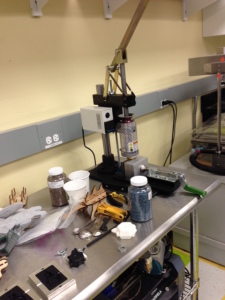

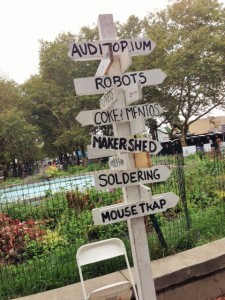

Stanford’s Fab Lab

From the d. School, it was just a hop, skip, and jump away to Stanford’s Fab Lab. The difference between a Maker Space and Fab Lab? Not much. There were a lot of cool toys lying around both spaces — things a do-it-yourself-er might like to tinker with — such as 3-D printers, laser cutters, tools, and other widgets. This interest in Making as Learning that’s grabbed hold of educators is no doubt the result of more equitable access to formerly high-priced items such as 3-D printers. Dale Dougherty, founder of the Maker Movement, discusses in the following video how Making is making its way into education. I showed this video at the Yavneh Academy Board of Education meeting that took place as soon as I returned from my trip. It got us all thinking about ways we might include Making in the curriculum:

Stanford’s Fab Lab:

The Fab Lab had the same sort of playfulness we encountered at the d. School. “Who says work can’t be fun?” was a recurring theme throughout the day — from Google to our meeting with Lee to the d. School and Fab Lab

Day 2

Professor Ari Kelman

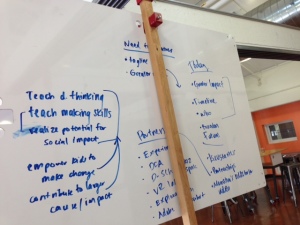

It’s hard to believe all that I just wrote happened on one day, but that’s what camp — I mean, a serious business trip — is like. Day 2 was just as much of a learning experience. Matt, Sabrina, Michael, and I began the day with Professor Ari Kelman, the Jim Joseph Chair in Education and Jewish Studies at Stanford’s Graduate School of Education. Just reading the book titles in Professor Kelman’s office was an education, but Ari, like Lee, also generously shared his wisdom with us. Ari — and Matt — study the Jewish ecosystem, so hearing the opinions of those studying the field of Jewish education from 30,000 feet high was important: those of us who are busy with managing what on some days feel like tiny twigs can sometimes lose sight of the forest.

The Los Altos School District

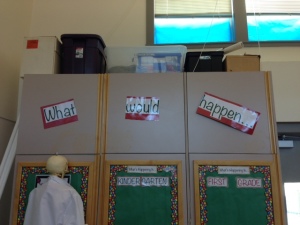

One place that is busy tending a very well-run forest is the Los Altos school district, our last stop before we headed on to our next adventures — more about those in another blog post. Visiting Los Altos brought our trip all together: the district engaged in Design Thinking to create its teacher training program. In fact, the teachers’ professional development rooms looked exactly like the d. School.

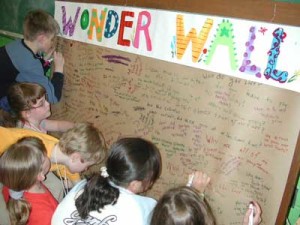

The district also had created an exciting STEM program, decorating its STEM classrooms in inviting ways that inspired students to create and innovate. We peeked in on a group of 8-year-olds who had been given the challenge to balance a LEGO house on no more than 10 index cards without being able to use scissors or glue. The first girl who completed the task did so in about ten minutes, but the truth is that all the students who entered this self-selected class began ideating and iterating from the moment they walked into it. Their motivation reminded us that when students never stop being curious and always look at work as play, then what results is the kind of joyful learning that takes place in kindergarten — and places such as the d. School and Stanford’s Fab Lab.

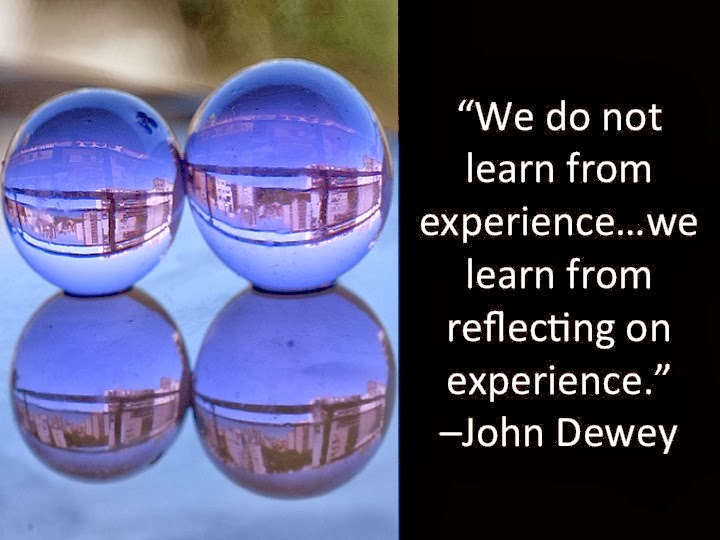

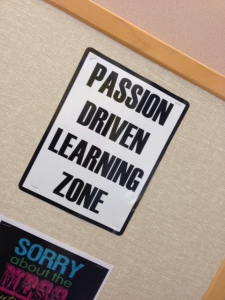

Passion-driven learning creates high levels of engagement — in students in the Los Altos school district as well as in employees at Google who have their passion-driven hive communities within the company

. . . and quotations. This one, of course, underscores the fail forward mentality we also saw at the d. School and the Stanford Fab Lab

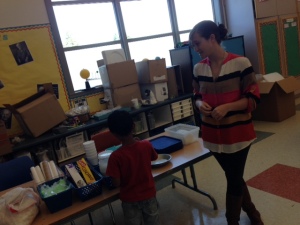

Teacher Katie Farley instructs her students on what to do for their LEGO Challenge, a task the students are willingly undertaking during their lunch period. Katie, by the way, taught at Maimonides day school in Los Angeles!

Sabrina, Michael, and my trip to Northern California, as I said, came full circle in many, many ways. Here’s a dot which connected our first and last two stops: did you know Google’s first servers were on . . . LEGO?

The teacher training rooms at the Los Altos school district were designed by the d. School’s K-12 Teaching Team

Shades of the Summer Sandbox: the pail as pen holder! And note the d. School-mandated post-it notes.

Takeaways

I’ve been thinking about learning as play for quite a few years now, but it’s a very different thing to think about it than it is to see it in one of the country’s top universities and enacted on a district-wide level in one of the most innovative school districts in the country.

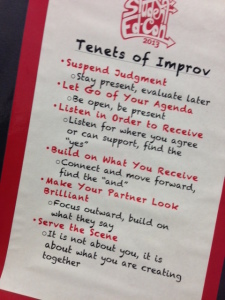

If you’ve been toying with how to begin playing, innovating, making, or designing in your school or classroom, but have been afraid to, perhaps you’ll be inspired by what’s going on in Northern California. And also remember how we began this post — by reminding ourselves to get out of our comfort zones. The Los Altos schools make sure their teachers do so by posting these tenets from the rules of Improv, an art form that demands that players remain open to what their partners throw at them. In other words, Improv requires a growth mindset as opposed to a fixed one, something the curriculum planners at Los Altos told us was at the heart of their professional development plan. We hope it will be at the heart of yours too: