Judaism is a religion that has thrived, been transmitted and stood the test of time on the value of questioning in order to seek, pass on and ensure the integrity of the truth. The Jewish people were given a written Torah that is often intentionally ambiguous, that without the oral tradition could not be fully understood or applied. The sages are constantly asking questions on the written Torah, debating the application of the oral Torah and seeking and explaining the answers to the questions that are raised. As Rabbi Jonathan Sacks beautifully states, “Judaism is the rarest of phenomena: a faith based on asking questions, sometimes deep and difficult ones that seem to shake the very foundations of faith itself.” We do not shy away from questions. Just the opposite. We require them. This becomes clear to us at the youngest of ages when we are taught our first pasuk of Torah.

When Jewish children are introduced to the Chumash, they are quickly made aware of what is bothering Rashi, the great Torah commentator. When they begin to learn Mishnayot and Talmud, the questions raised and the debates that ensue are paramount to the truth-seeking process. How about the Pesach Seder, which hinges on the achievement of engaging the youngest of attendees to ask questions? It is truly beautiful! The entire process of Torah learning is one that is driven by questions, which is why, I suppose, I am very fond of Project-Based Learning (PBL).

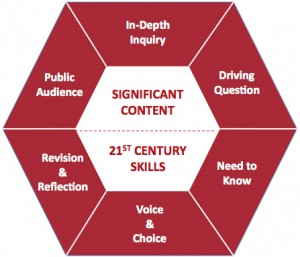

Project-Based Learning is, at its core, an inquiry-driven approach to learning. Of the eight elements that make up PBL proposed by the Buck Institute for Education, the Driving Question is the most critical, as it is the element that lays the foundation of the project and propels it forward to its completion.

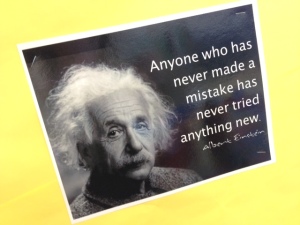

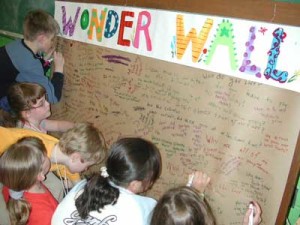

“There are no stupid questions” was the mantra I heard in almost every first day of class growing up. Most students understood this to be an invitation to ask questions; most of my teachers might have said I took it as a challenge. However, what most of us learned growing up in school was that the invitation (or challenge) was an empty one. Very little time was given to student-formulated questions. Sure, we were sometimes allowed to ask for clarification, but we were never taught how to ask the important questions. In fact, most of the questions came from the teachers when, after an hour of giving us answers, asked us if we understood. So, real questioning became an exercise in isolation for many of us. As Chuck Close poetically put it, “ask yourself an interesting enough question and your attempt to find a tailor-made solution to that question will push you to a lonely place where, pretty soon, you’ll find yourself all by your lonesome - which I think is a more interesting place to be.” However, in PBL, questioning does not have to be a lonely place and, when done well, is certainly “a more interesting place to be” in and out of the classroom.

According to the Buck Institute for Education (BIE), “a good Driving Question captures the heart of the project in clear, compelling language, which gives students a sense of purpose and challenge. The Question should be provocative, open-ended, complex, and linked to the core of what you want students to learn. It could be abstract (When is war justified?); concrete (Is our water safe to drink?); or focused on solving a problem (How can we improve this website so that more young people will use it?).” Andrew Miller, who I have had the pleasure of learning from multiple times and is an expert in PBL, bluntly and correctly writes that “Driving Questions can be a beast.” Amen, brother! They can be a beast in all the best ways a beast can be, if that makes any sense. However, Mr. Miller shows us how to tame the beast in this article on how to write driving questions.

The Driving Question is literally that. It is what drives the project. As the BIE continues, “ A project without a Driving Question is like an essay without a thesis.” It is a primary element that differentiates PBL from just a project. The Driving Question creates a continuous thread that ties the learning, the project, and often its real-world application together from start to finish. Without this, and many of the other elements of PBL, the project is just another activity among various activities that make up a static learning unit. Yes, the activities are part of an overall theme or learning goal, but if not thoughtfully connected, they can feel disjointed and appear irrelevant to the learning process. Having a Driving Question ensures everything that is done in a PBL unit is connected and focused on answering the question. The project is not the goal. Answering the question is the goal. The project is the learning process, as well as the outcome of the learning, in service of answering the Driving Question. This is unlike a project alone which is generally, at best, a representation of the learning, but more often than not, just a product of one singular activity among a series of disjointed activities in a unit.

Hopefully, this clarifies how the Driving Question is an essential element of PBL. I would also advocate the use of inquiry and the teaching of meaningful questioning, even if you do not use PBL. Suzie Boss, journalist and PBL advocate, recently wrote a great article for Edutopia that is resource-filled and focused on using student questions to drive learning. This would be a great place to start in understanding the use of questioning in the classroom and with that I leave you with this: What is the best way to teach students to formulate a good question? Drive on!

Recent Comments