Problem-Based Learning, as its name suggests, asks students to solve a real-world problem. One thorny problem Jewish educators face is how to approach prayer — tefillah — in school. At the PBL Collaboratory in Judaic Studies that took place last month in late March, a group of us were inspired by RealSchooler Ronit Langer, who dropped by and spoke about the fact that tefillah in school seems more punitive than aspirational. We decided to tackle the topic during our project design session.

As we pondered the dilemma, Yeshivat Noam’s Ms. Aliza Chanales helped us gather our thoughts, in her typically humorous and cut-to-the-chase manner: “We would never intentionally design an educational experience this way: When else would you put kids in a room together for forty minutes and tell them to sit straight, not talk to each other, and not let half of the room participate in a significant manner [referring to Orthodox prayer services]?”

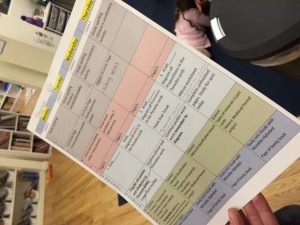

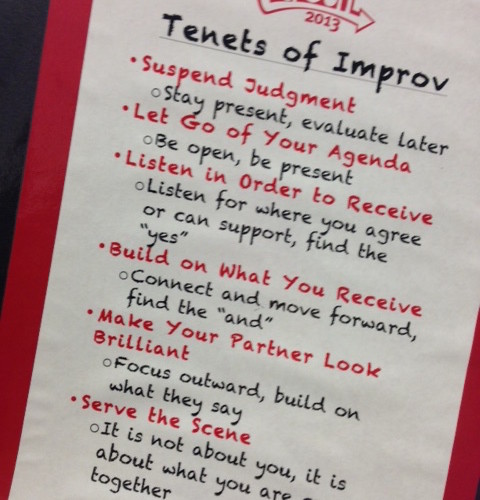

We all sighed. Ben Porat Yosef’s Educational Technology Director, Mrs. Shira Ackerman, and I decided to brainstorm some solutions. Using the Buck Institute of Education’s Project Design template, we asked ourselves how we might create a more engaging tefillah experience.

We noted that many schools have already initiated tefillah programs that incorporate yoga, meditation, or other activities that appeal to students and might put them in a prayerful mode. Some schools even replace prayer with communal work. We decided that for our project we would maintain the structure and content of the traditional tefillah service.

Here’s the emerging PBL unit, which Shira and I offer for critique and feedback:

Name of Project: TEFILLAH REDESIGN

Subject/Course: JEWISH PHILOSOPHY/LAWS OF PRAYER

Other subject areas to be included, if any: Tanakh, History/Jewish History, Math, English, Science, Educational Technology, the Arts, Design Thinking

Significant Content: The disciplines we chose to subsume this project under — Jewish philosophy and Laws of Prayer — imply students will be studying why they pray or the laws of prayer, respectively. However, the truth is that teachers can access the project any way they want. Based on who is teaching the course and in what discipline it grows out of, teachers can choose to focus on a particular subject.

Project Summary: Using the model of an inquiry-based classroom and student voice and choice, students explore tefillah through a lens that is meaningful to them. For example, a student interested in history might explore the history of prayer, when the different prayers made their way into the service, and how they might differ in myriad communities.

A student interested in Tanakh could explore the sources of our prayers, while someone interested in science could create significance around the tefillot that praise God for making our bodies work properly and creating order and wonder in the natural world. Still others could use interest in music to study the history of melodies in prayer, and a student of the visual arts could visually interpret prayer.

If the problem or challenge students tackle in the project is how to make prayer relevant and engaging to themselves, then this research-based first part of the assignment is designed to tap into a personal passion or interest. However, we decided we also wanted students to think about how to interest their co-religionists in prayer. The second part of the project, then, requires students to interview each other and those outside their school about the meaning of prayer in their lives.

We also thought it would be important for students to pray with people other than peers. They should have rotations where they pray with the community and with kindergartners, who have a natural enthusiasm for prayer.

The design thinking challenge we then set for our students would be to collect data about who prays best and when and why enthusiasm for prayer wanes. The students would then have to create their own solutions for engaging students in tefillah. They also would incorporate into their solutions the research they conducted in a particular discipline.

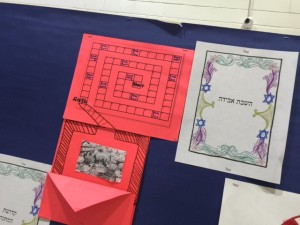

One final product of the project would be individual prayerbooks, based on what was compelling to each student and with room for the student to add to his/her reflections. The second final product would be a plan born out of the design thinking process for how to increase student engagement in tefillah. The students who prepared the plans for the school would present them to the student body, who would then vote on the best plan. The school would implement that plan.

Driving Question: How might I find meaning in tefillah? How might I make tefillah meaningful for my community?

We realize we haven’t filled in all the parts of the BIE template, but you can get a feel for how we would do so from what we’ve included so far. We chose these approaches, because they include individualized ways students can connect to prayer — through personal interests and passions — and theyalso require students to connect to those beyond their classroom, to people in their community of all ages, from the very young to the very old. The project could include going to a home for the elderly, praying with residents and asking them why they pray. In PBL, connecting to the outside world is a vital part of the learning experience. Here it could take on deep affective significance.

At the North American Jewish Day School Conference in early March, I worked with educational consultant Jonathan Cannon and educators Drs. Eliezer Jones and Yechiel Hoffman on a session that audaciously told participants that all their assumptions about day schools are wrong. In Jonathan’s (rather entertaining) introduction to the session, he mentioned that our schools seem resigned to the fact that certain parts of the Jewish day school experience might not be working. Prayer, Jonathan implied, is something JDS needs to fix.

I recently read Switch, the wonderful book about change by Dan and Chip Heath. The authors talk about how to create change, even for situations that seem intractable. One way to do so is to focus on bright spots — things that are working. We tried to do that in our tefillah project, by enabling students to experience prayer with those who are enthusiastic about it — the very young —; those who are consistent about it — the adults in the community — ; and those who are wise about it — the very old.

As Aliza, Shira, and I worked, we even bandied about the idea of having students pray every day with the adults in the community. If PBL really is about connecting to the real world, then nothing could be more real than having students pray with their community. It’s an idea I’ve heard other educators speak about as well, and one which would allow school to begin later for students. A later start time in schools would allow us to take advantage of developments in neuroscience that tell us adolescents benefit from not waking up at the crack of dawn.

What I especially liked about tackling this project with my colleagues was a sense of empowerment, of considering the notion that we aren’t necessarily stuck with the system we’ve inherited and that new solutions are possible. Considering the new and engaging in big dreaming is one of the main attractions, for me, of problem-based learning, as is collaborating with peers. I know these are attractions for students as well, so it was a logical progression for Shira and me to have the students come up with their own solutions for the problem of prayer in school. A fresh look at the dilemma, from those most deeply affected by it, seems like a good idea.

However, we welcome everyone’s feedback on the project and look forward to hearing if anyone has tried any of the ideas we’ve mentioned and if so, how those ideas have fared. We also welcome suggestions that would project tune the PBL unit.

In the meantime, enjoy this found poem RealSchoolers created from linking together different students’ responses to what worked for them in tefillah. All this talk about the problems with tefillah made us realize we might want to end with a bright spot:

I like davening [praying]

In silence

And at my own

Pace.

Davening is peaceful

Meditation

And gives me time

To reflect on my

Day and what

I’ve done.

Tefillah is important

To me

because

When I’m down

Or without hope,

It gives me

Faith

And a purpose

In life.

I like having a set

Time

To communicate with

Hashem [God].

It forces me

To continually refresh

The relationship.

I like the personal

Aspect of tefillah,

Not only reading

The words

But making them

My own.

Tefillah gives

Me the feeling

That I always

Have someone

To lean on.

It gives me

A chance to pour

Out my feelings to Someone

And to thank Him

For everything

I have.

It makes me

Feel like God is listening.

Recent Comments